Hamilton: The Workers' City

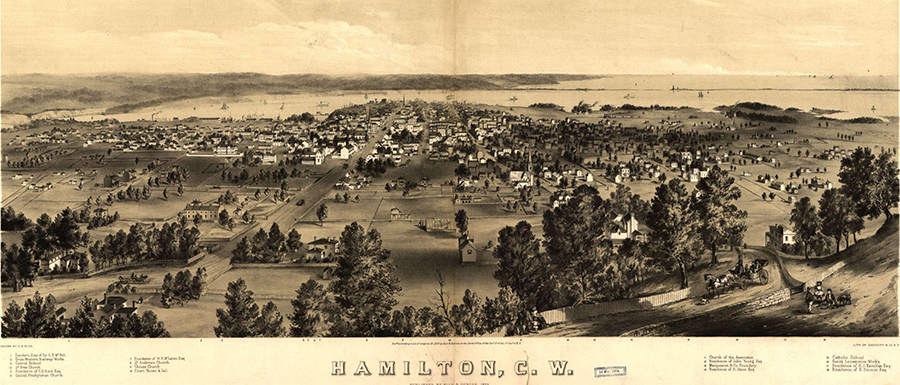

A Growing City

The land for the city of Hamilton was deeded in 1816, on the site of present-day Gore Park. The city was incorporated in 1846.

The opening of the Burlington Canal in 1820 helped Hamilton become an important port city. The coming of the railway in the mid-1850s spurred the city’s development, too. Hamilton’s booming economy attracted immigrants from the United Kingdom, the United States, Italy, and Poland, among other countries. Immigrant labourers contributed greatly to the city’s economy and its community.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Hamilton was one of Canada’s most important industrial centres, a role it continued to occupy for decades to come. Firms such as the Steel Company of Canada, which was formed in 1910 from a merging of a five smaller companies, would become one of Hamilton’s most important industries and employers, as well as a stronghold of industrial unionization in the city.

Working Life in Hamilton

For many of the workers employed in Hamilton’s industries, though, jobs were precarious and life was harsh. Family members, including children, worked long hours for low pay in unsafe and difficult conditions.

Clerical Workers

Until the 1890s, only men were employed at city hall. But as recording and sending information became more important, women began to obtain jobs as stenographers. As the typewriter gained popularity, these jobs were increasingly characterized as “women’s work.” By the mid-1920s, around 50 women were working at city hall. They were classified as clerks and received lower wages than most other “inside” workers, including men who performed similar duties.

In later decades, the clerical workforce expanded and women began to break into other professions. By the time of the 1973 strike, a majority of Local 167’s membership were women.

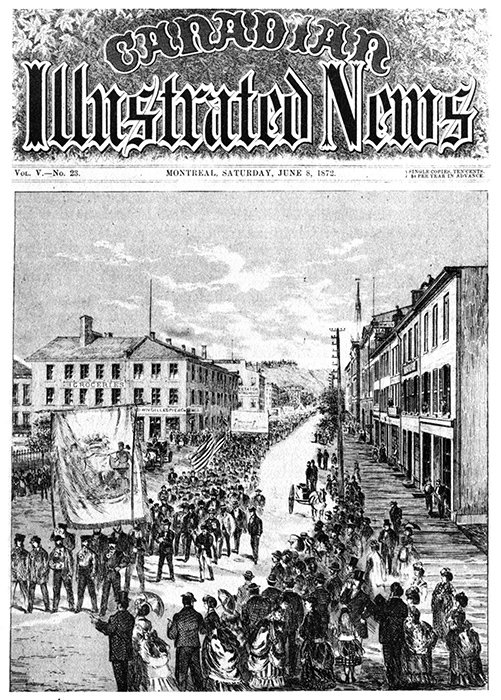

Fighting Back

Over time, working people in Hamilton organized and fought back against these conditions. Craftsworkers banded together as increasing mechanization allowed employers to use many more unskilled workers, and to devalue their work. The Nine-Hour Movement, an international workers’ attempt to secure a nine-hour working day, held its first march in Hamilton on May 15, 1872.

The first Canadian assembly of the Noble and Holy Order of Knights of Labor, an important labour reform organization founded in Philadelphia in 1869, was formed in Hamilton in 1875—its first chapter in Canada.

Workers’ militance and strength gained momentum in the early 20th century. In November 1906, the Hamilton Street Railway workers, Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America (AASEREA 107), went out on strike over long hours and low pay. The strike turned violent after managers try to keep the system operating. Hamiltonians showed their support for the strikers by wearing blue “We Walk” buttons.

In the wake of the strike, Knights of Labor organizer Allan Studholme was elected as an independent labour MPP in the Ontario Legislature. He was the province’s only labour MPP until 1919, and a sign of the growing political strength of Hamilton’s working people.

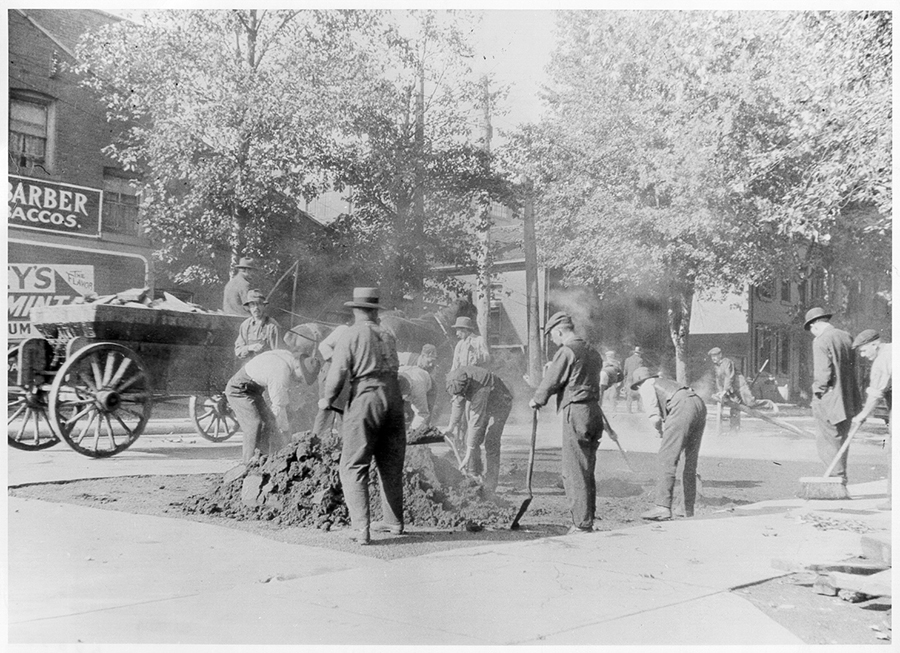

Civic Workers Begin to Organize

As the population of Hamilton grew, so too did the need for municipal services. More Hamiltonians found jobs with the city, both as outside labourers and inside workers. Soon, these workers began to form employee associations to help them gain better wages and working conditions. In the late 1800s, civic employees began organizing into unions.

Fighting for shorter working hours and better pay was a key focus of the civic workers’ fight. For example, wages for general labourers were 13.5 cents per hour in 1890; 10 years later they were making just 15 cents. On August 1, 1900 the rate was boosted to 18 cents after a successful campaign organized by the Civic Employees Union, and then 22 cents in 1913. In 1900, Hamilton quarry workers, who were members of the Civic Employees Union, went on strike for better working conditions. They were also joined by road and sidewalk workers.

Garbage Workers

For most of the 20th century, garbage was collected in large, open trucks or carriages, and workers were under constant pressure to increase their efficiency by piling garbage higher and higher. This led to numerous back and shoulder injuries and some very bad falls from piles of garbage that could be as high as five metres off the ground. Local 5 argued that covered trucks, with mechanized loaders, would reduce rates of injury, but it took a long time to convince management, who insisted that the most economical choice — the open truck style of garbage collection — was best.

Time for Fun and Family off the Job

Civic workers formed strong bonds off the job, too. In the summer of 1912, for example, 1,500 of them attended one of the city’s first annual civic employees’ picnices, which was held at Grimsby beach. It was a tradition that would continue for decades. The workers’ employees’ associations and, later, their union locals, also organized Christmas parties, Valentine’s Day dances, bowling tournaments, and many other social gatherings.

Heading to War

By 1913, an economic recession had begun to erode some of the gains that civic workers had fought for. In 1914, the coming of the Great War would help put many Hamiltonians back to work in war-related production and in many other industries. But it would also bring unprecedented death, destruction, and change.