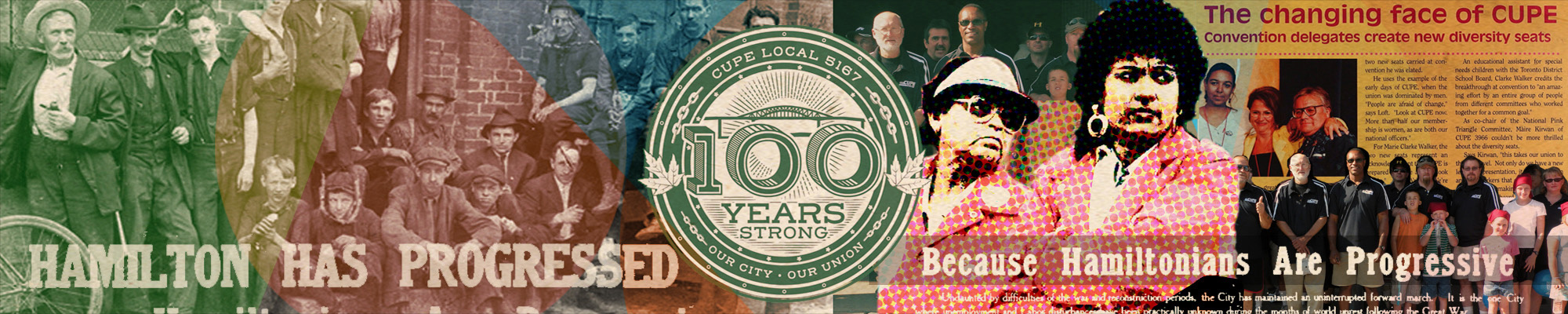

From Depression to War

Hardship and Upheaval

The 1930s and ’40s were a time of important social, political, and economic change in Canada.

The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 plunged millions of Canadians into poverty and unemployment. Depression was replaced by war in 1939. Across the country, major industries retooled to make war-related products, such as those produced at Hamilton’s Westinghouse. Many Canadians signed up to serve overseas. High unemployment was replaced by chronic labour shortages and a wave of militant unionization and strikes after the war.

“It’s hard for some people to comprehend today the extent of unemployment. It was massive…. Unlike today, where the unemployed are virtually voiceless and unorganized, in the ’30s the unemployed were highly organized…. There were thousands that belonged to the unemployed. It was basically men. Women weren’t considered unemployed. There were a number of unemployed men’s organizations. Some of them were organized around being veterans of World War I. There was sometimes distinctions between married unemployed and single unemployed. But nevertheless, it was massively organized. They were active in demonstrating for jobs, demonstrating for adequate welfare, it was called relief in those days.”

– Gilbert Levine, CUPE’s first Research Director; interviewed by Don Bouzek, Alberta Labour History Institute, December 2004

The Great Depression

On October 29, 1929, the biggest stock market crash in history ushered in the Great Depression. Over the next 10 years, the “Dirty Thirties” forever changed the lives of workers in Canada and around the world. In Hamilton, 51% of men and 33% of women lost their jobs or had their working hours drastically reduced during the Depression. This was the highest number in any Canadian city except Windsor.

Across the country, governments tried to cope by creating relief programs for unemployed men. The programs often focused on large infrastructure and building projects. In Hamilton, the city funded a $2 million work-for-relief program. Projects such as the city’s northwest entrance and rock garden, a hospital on the mountain, sewer installation, playground construction, road construction, and alleyway paving were all completed by unemployed labourers during the 1930s.

Sam Lawrence

Sam Lawrence was born in 1879. He was a stonecutter, trade union activist, and the mayor of Hamilton from 1944 to 1949, leading a CCF slate of candidates. Lawrence is remembered for his support of workers in the bitter Stelco strike of 1946. He led a march of more than 10,000 people to the gates of Stelco in the midst of the strike. Lawrence also won elections for alderman, controller and MPP during his political career.

Fighting Back

But working people fought back against these difficult conditions. Unemployed relief camp inmates drew national attention to the plight of the unemployed during the On-to-Ottawa Trek in 1935. The trek was sparked by the harsh conditions in federal unemployment relief camps: 1,500 residents of camps in British Columbia, led by the Communist Workers’ Unity League, stopped working and travelled by train and truck to Vancouver, Regina, and Ottawa to protest their living conditions. The strike leaders were eventually arrested, resulting in the Regina Riot.

On the political front, the Co-operative Commwealth Federation (CCF), a coalition of progressive, socialist, and labour groups, was founded in Calgary in 1932. The new party wanted economic reforms that would help Canadians during the Great Depression. One of its founders, Tommy Douglas, later became the premier of Saskatchewan and the first leader of the New Democratic Party in the 1960s.

Civic Work During the Depression

The Depression was a difficult time for Hamilton’s civic workers, as it was for all Hamiltonians. In 1932, for example, workers were forced to accept a voluntary salary reduction, beginning in 1933. On the first $1,000 or less of a worker’s salary, 5% was cut. On the second $1,000, 15% was cut; on the third $1,000, 20%; and on the fourth $1,000, 25%. All those making over $4,000 a year had to take a 30% pay cut. Hourly employees’ wages were reduced by 10%.

The 5% cut was not restored until 1936, and the remaining 5% in 1937. Workers were given six paid statutory holidays and had to work a 44-hour week, except for the cemetery department, which worked 48 hours a week.

By 1935, workers’ frustration with these cuts had boiled over. Relief workers went on strike to protest the low pay, which they considered to be barely at subsistence level, and poor working conditions.

But many civic workers were struggling just to keep their jobs. City managers took advantage of the high rate of unemployment to hire relief recipients at a fraction of the cost of their regular workers. Street maintenance department staff were hit particularly hard: around 100 of them lost their jobs. Workers with as much as 30 years’ seniority were replaced and their families were forced to go on relief.

The strikers believed they were being unfairly exploited. They were doing jobs that used to be well paying, and that now involved working in dangerous conditions, often outside in unforgiving weather. The city argued, though, that it had hardly any money to maintain its sewers and road crews, let alone give the workers more money.

World War Two

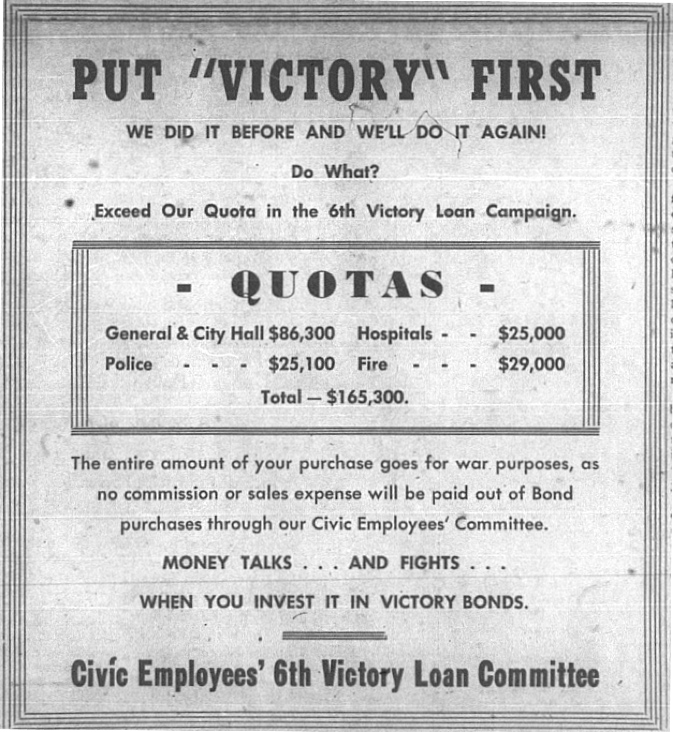

Canada entered World War Two in September 1939. Twenty thousand Hamiltonians voluntarily enlisted in the war effort. By the end of the war, 4,000 of them had been killed or declared missing in action.

Labour shortages and high inflation caused a wave of unionization: union membership rose 85 percent in Canada during the war.

Hamilton’s industries were transformed by the war. Machinery in large factories such as Westinghouse and National Steel Car was re-tooled to create war material and supplies. By 1942, 60,000 Hamiltonians worked in these industries, and many more workers were needed. Women also began working in these factories, replacing the men who had gone overseas to fight.

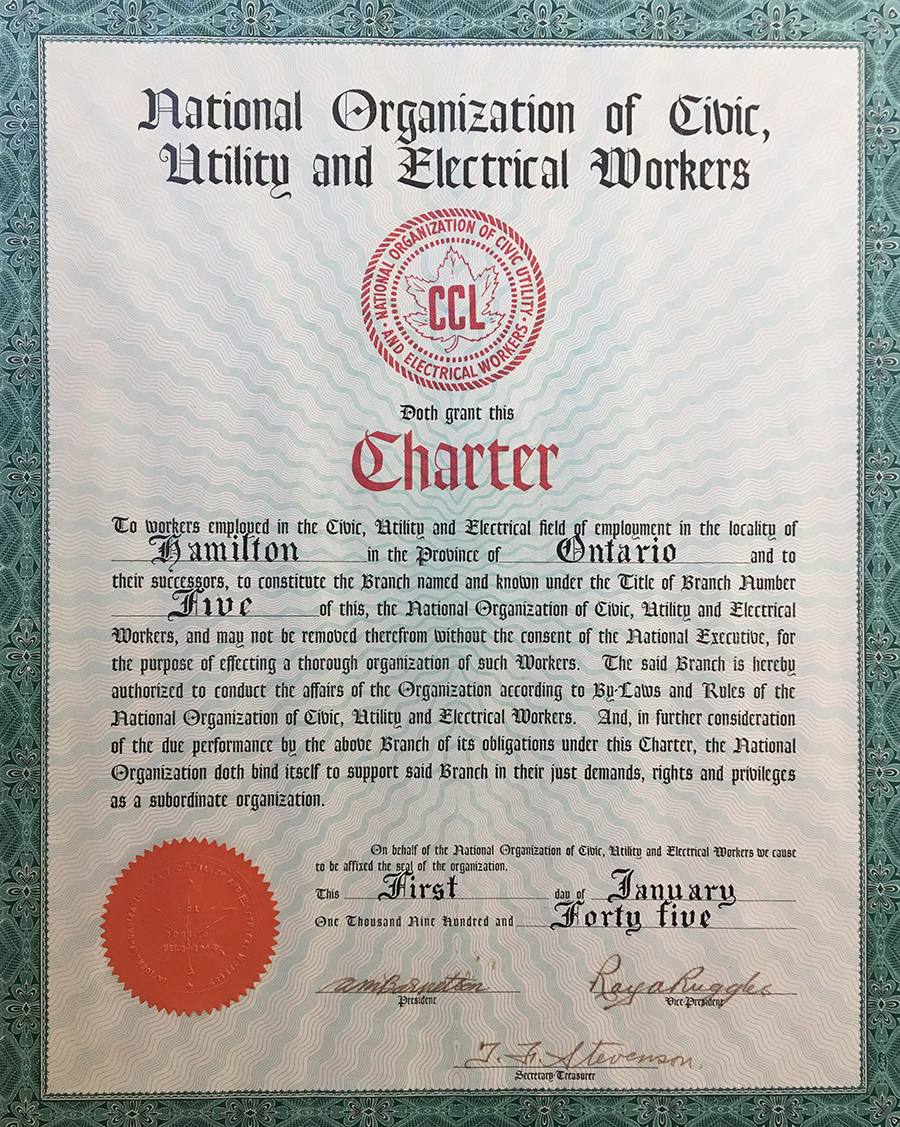

The Birth of Local 5

In April 1933, Hamilton’s outside civic workers chartered with the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada to form the Hamilton Civic Maintenance Association, Local 33. Ten years later, in April 1943, the Local chartered with the new Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) to become the Hamilton Civic Employees Union. The next year, 1944, Local 5 of NOCUEW (the National Union of Civic, Utility and Electrical Workers) was born. In 1952, NOCUEW became the National Union of Public Service Employees (NUPSE).

In 1944, Local 5 had about 1,000 members. It negotiated its first contract with the city, which remained in place until 1949. Its demands included a 40-hour week for 44 hours of pay and a 10 cent-an-hour increase for all members.

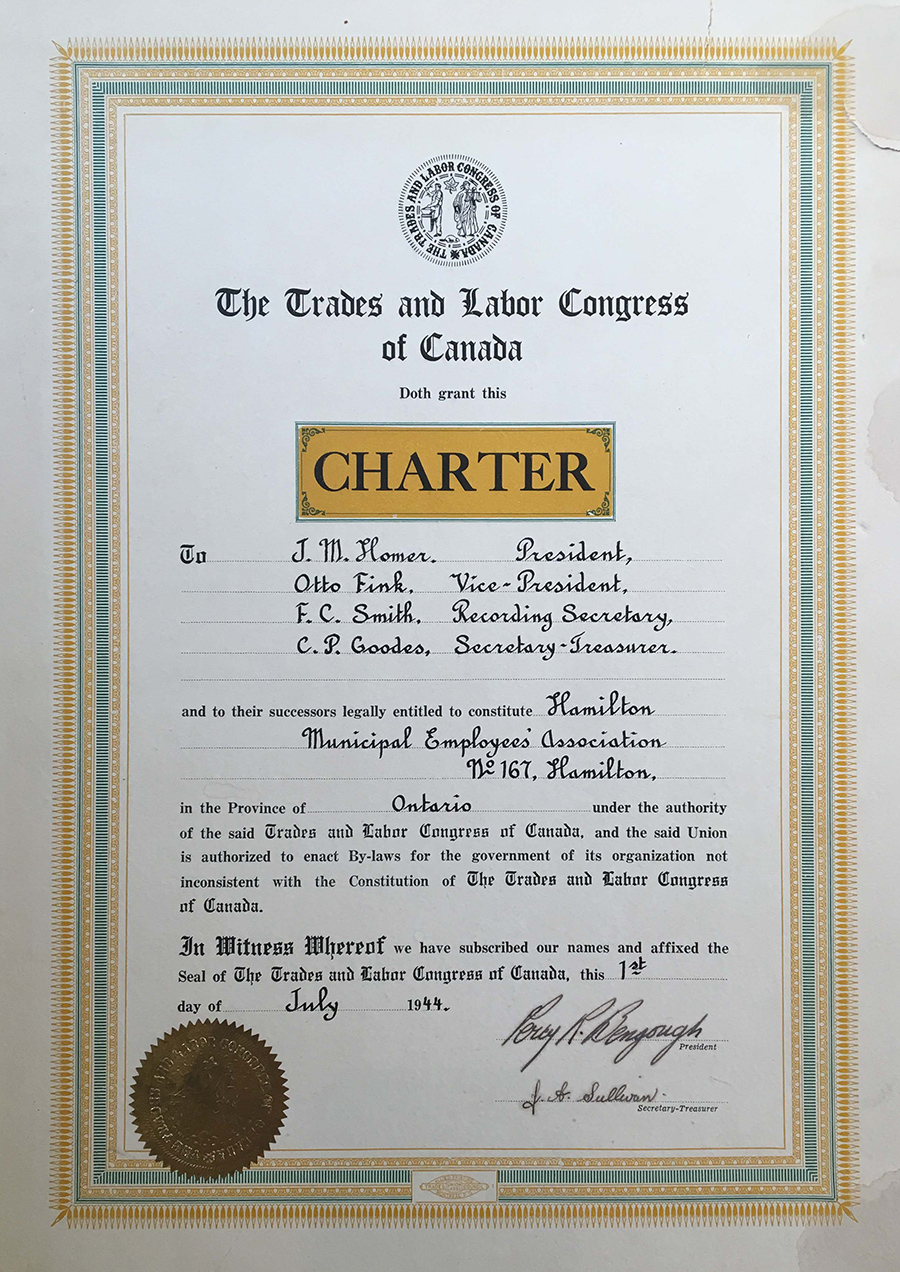

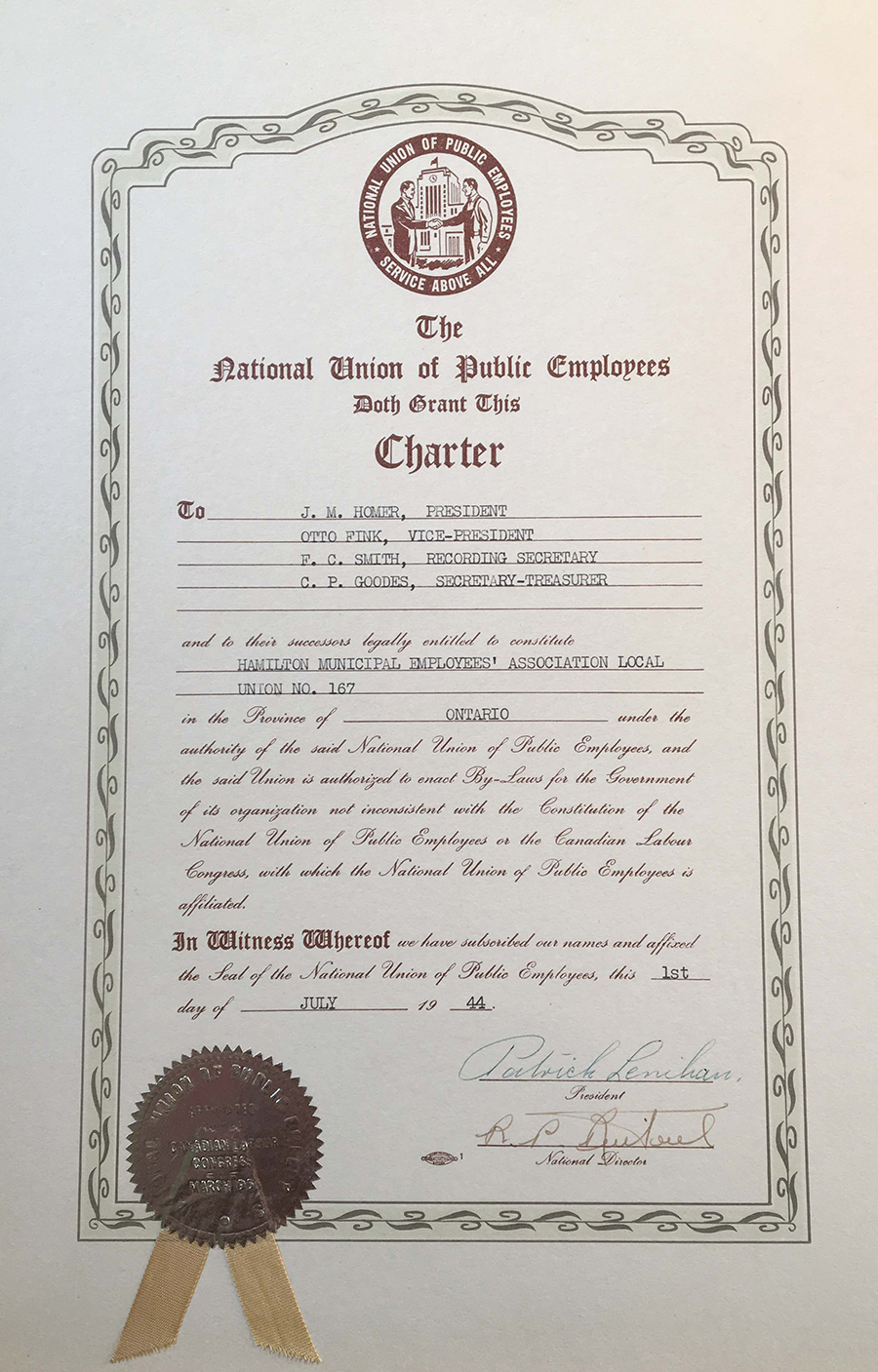

The Birth of Local 167

Inside workers also went through significant organizational changes during the 1930s and ’40s. By 1934, the Civic General Staff Association represented about 350 inside civic workers. On April 25, 1944, the inside workers chartered with the CCL to become the Hamilton Civic Employees Union. Two months later, on June 20, they chartered with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to become the Hamilton Municipal Employees Association, Local 167. The Local’s first president was J.M. Homer.

The new union’s first contract was, like the outside workers’, signed in 1944, on July 25.

Wartime Gains

The coming of World War Two in late 1939 jolted the country out of recession. The unemployed began to find work. Civic workers began to regain much of what they had lost during the Depression.

Civic workers gained other benefits, too. A pension plan was finally established in 1944 for the city’s 800 eligible employees. Workers paid 5% of their earnings into the plan, which would provide an annuity of $15 per year multiplied by the number of years of service after the age of 25. The maximum annual pension was set at $600 for men and $535 for women. City council passed a motion in late 1943 to approve the plan, which required the city to contribute $112,000 each year for 30 years.

Nationally, the first compulsory national unemployment insurance system in Canada was introduced in July 1941.

Strengthening Bonds off the Job

Although both the Depression and World War Two had been very hard on workers and their families, they still found ways to gather together and strengthen their bonds. Attendance at picnics, dances, Christmas parties, and bowling tournaments grew.

In July 1934, for example, 6,000 civic workers and their families attended the annual civic picnic. Events included baseball, a baby show, and a vaudeville-style show. Prizes such as lamps, food, and dishes were handed out to the winners. And in 1943, 1,960 workers and their families attended the 28th annual Civic Employees’ Picnic at Port Dalhousie.

Post-war Change on the Horizon

Once the war ended, in 1945, life for working people and their families became easier. Civic workers would enjoy significant gains and changes over the next 25 years as Canada’s economy boomed.

Timeline

*bold events on the timeline are specific to Local 5167