Austerity and Struggle

Slashing and Burning

The mid-1970s ushered in the first era of post-war government spending restraint. As oil prices rose steadily and inflation ballooned, the federal government implemented wage and price controls.

In response to soaring inflation rates (12.6% in 1975 alone), the government created the Anti-Inflation Board (AIB) to try to control wages. The AIB capped wage rates at 10, 8, and 6% per year between 1974 and 1978, and all bargaining became subject to AIB approval.

High inflation rates continued into the early 1980s, averaging 11.5%, and the unemployment rate reached 11%.

Other measures included the Inflation Restraint Act (Bill 179), which limited public sector wage increases to 5%, eliminated the right to strike, and extended current collective agreements by one year — taking away the right to bargain for higher wages in that time.

“When I first started I started working as a labourer in the 1970s, there was still a lot of manual labour to be done. We used to shovel school walkways, around the whole block, 14 people shovelling. Now they have plows and stuff like that. The odd time I’d work the garbage route, in what they’d call the open truck — bird cages — before they had street packers. There’d be cans rather than bags. Two guys on the ground and one guy at the top, bringing up the garbage — the guy on the top’s all, maggots and everything, right. It was tough.”

– Ed Thomas, Local 5 member and activist

Municipal Amalgamations

In the early 1970s, the province enacted legislation that introduced new regional government structures. In Hamilton, city workers were divided into two groups: The city retained the street and sanitation departments, parks and recreation, cemeteries, golf courses and ski hills, while the new Hamilton-Wentworth regional government took over the sewer and water department and the regional roads and highways that passed through the city.

“We supported other organizations outside of our own. We were very close to steel workers and other private sector unions, and the labour council. Hosted striking workers up north too. Through the labour council we’d do things and express ourselves under their banner.”

– Jim McDonald, former Local 5 President

Fighting the Cuts

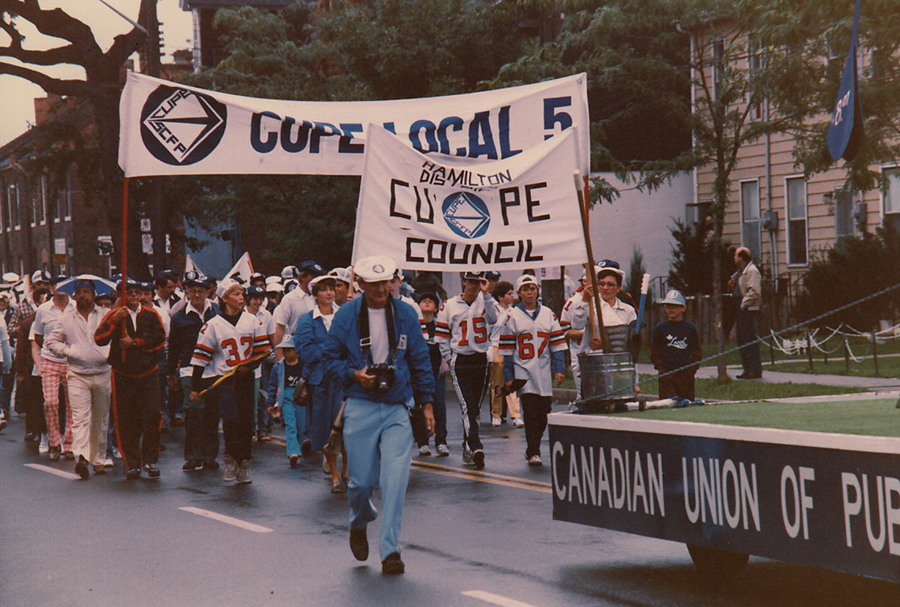

As economic uncertainty grew, workers’ gains were eroded. Many large-scale strikes were held across the country as working people fought back against the cuts. On March 13, 1975, the Hamilton and District Labour held a mass rally against the government’s wage control program. Many union Locals, including 5 and 167, attended the rally. And on March 22, 1976, the Canadian Labour Congress held a similar rally in Ottawa, which many Hamilton civic workers attended.

For civic workers, like other workers, it was a constant battle to keep up with inflation and government cutback legislation. Locals 5 and 167 bargained contracts in the 1970s that pushed wages up by 18% over two years, as inflation rates crept into the double digits.

Enough is Enough! The 1973 Strike

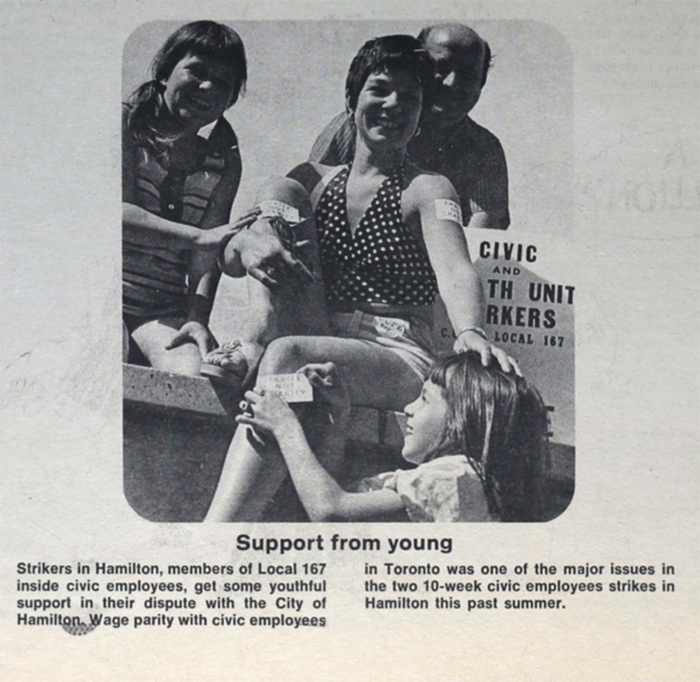

On July 11, 1973, after a number of fruitless bargaining sessions with the city, Local 5’s garbage workers walked off the job. The 1973 strike was the biggest job action in the Local’s history: It lasted 68 days, until September 17. Emergency dump sites were set up across Hamilton. On July 30, Local 167’s inside workers joined the picket lines and, later, so did the Board of Education workers, Local 1344.

The main issues were wage parity with Toronto civic workers and a cost-of-living allowance that would help wages keep up with runaway inflation. This would require increases of 15.6%, or 58 cents an hour in one year. Wage rates at the time for garbage workers ranged from 3.58 to $4.36 an hour.

As the strike wore on, many Hamiltonians rallied around the strikers, as they had more than two decades earlier. Thousands of people signed a petition asking city council to get back to bargaining in good faith and to include a cost-of-living allowance for garbage collectors. Others brought food to the picketers and joined them on the lines.

The long summertime strike did test some Hamiltonians’ patience, however, as garbage piled up and no end to the strike was in sight. On July 19, the Hamilton Spectator reported that “the city’s emergency dump at Wellington and Wilson streets developed into a battleground today as an army of neighborhood mothers and children tried to prevent people from dumping there.” “Don’t put garbage on our lawn” signs sprouted up at the makeshift dumps as the strike wore on.

By August, Locals 5 and 167 had begun working together to negotiate with the city during the strike, as it became clear that a coordinated approach would help them better achieve their goals. In the end, after numerous bargaining sessions, the strikers did realize some important gains. Their new contract included wage increases of 19.15% over the two-year contract period, or an additional $20 a week for each worker.

After the Strike

Although the Locals had begun to work together near the end of the strike, it was clear by the time the strike ended that both Locals needed a better, more coordinated approach.

In January 1974, a joint meeting was held between officials of Local 5, Local 167, Local 1344, and CUPE representatives. A new coordinating committee structure for negotiations was set up. It had three stated goals: to achieve common expiry dates, uniformity in bargaining goals and contract proposals, and joint bargaining sessions, when possible. This new “unity of purpose” would, CUPE hoped, help the Locals better prepare for negotiations, and win more at the bargaining table.

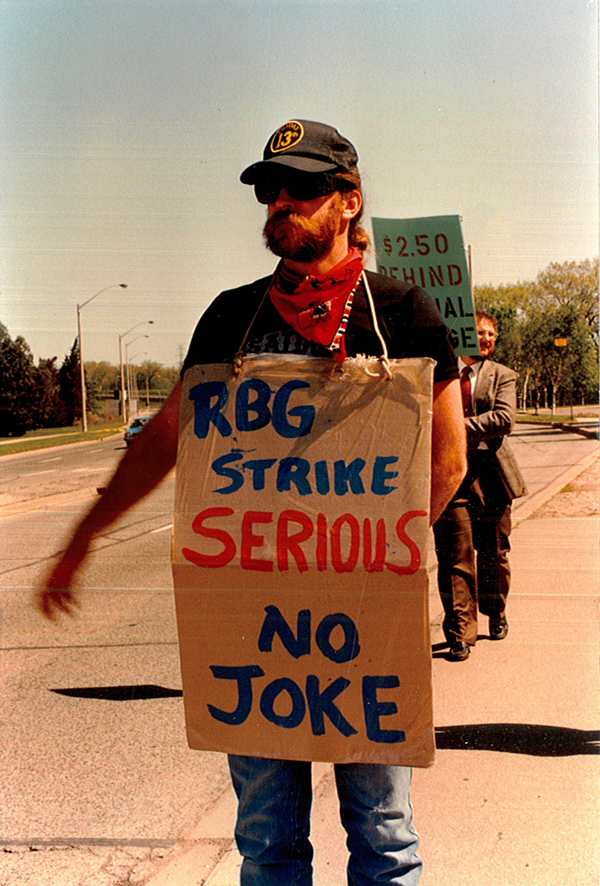

“There was a strike at the RBG in 1989. It got to the 11th hour — they thought we wouldn’t go on strike and were bluffing. But when they saw the picket lines the next morning, they knew we were serious. We had timed it two weeks before their lilac festival. Strategy was everything. When we settled, we got everything we asked for. It was the first strike ever at RBG. And there hadn’t been a strike since. You saw a lot of people who were not so much into the strike, but saw it as an important issue they wouldn’t walk away from. They realized their rights were being breached.”

– Sid Gratton, former Vice-President, Local 5

Strike at the Royal Botanical Gardens

In May 1989, workers at the Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG) walked off the job and into their first — and only — strike. Although the strike lasted just 10 days, it won important gains and was an education in solidarity for the unit’s members. Local 5 members from other units actively supported the RBG strikes, joining them on the picket line in a coordinated effort to keep the entrances to the gardens covered.

The RBG was one of Local 5’s smaller units, with a full-time workforce of just 30 people. This was complemented by seasonal workers and students during the summer months. The unit had evolved out of the City of Hamilton’s Parks Board, and the RGB itself was funded through the city.

What sparked the walkout was the RBG’s refusal to match the wage increases and benefits achieved by workers at the city. Job classifications and wage disparities were also key issues.

Although it was a short strike, it was a difficult one for workers, students, and volunteers at the RBG. Many seasonal employees were recent immigrants. Some of the summer students crossed the picket lines for fear of losing their jobs. And relationships between workers and volunteers became strained as some volunteers refused to honour the picket lines.

In the end, the RBG workers achieved everything they had been seeking. Wage disparities were reduced or eliminated, and new job classifications were put in place.

Sid Gratton talks about the 1989 RBG strike.

“The RBG was a non-profit organization and health and safety was at the bottom of their priorities; they thought they were exempt from the legislation. We really relied on the health and safety people from CUPE to help us set up our health and safety committee at RBG, although they didn’t have a terms of reference until 20 years later. A lot of orders were made by the inspector to RBG saying, ‘Yes, you have to do this, and yes you have to comply.’ It took about three years to get them to actually realize that they had to comply.”

– Peter Wickett, former Treasurer and Recording Secretary, Local 5

Sid Gratton describes the process of becoming a health and safety rep and helping to implement new guidelines at the RBG.

“When I started at the RBG in 1976, they had permanent full-time staff and permanent temporary staff. There was a seasonal layoff every year. There was a group of technicians or horticulturalists who were not laid off. And then there was this other group who were totally different. Some had education in horticulture from Europe, but RBG wouldn’t recognize that, so they were always in labourer positions. They got laid off every winter. Some of those guys had 20 years on the job. We had guys here, myself included, who had been on the job two years and weren’t getting laid off. In my mind, even before I got involved with the union, I thought that was an injustice. How can you do that?”

– Sid Gratton, former Vice-President, Local 5

Other Gains for the Locals, and for CUPE

Locals 5 and 167 did achieve other gains during this difficult era. In 1980, Local 5 became the first CUPE Local to successfully negotiate paid leave for union training. Employers would contribute one-half cent per hour for each employee in the bargaining unit.to a central fund for this training. Under the plan, the education department provided a residential training program consisting of 20 days of classroom time.

The membership of both Locals continued to grow. By 1985, Local 167 had five bargaining groups: the City of Hamilton, the Region of Hamilton-Wentworth, Health, Macassa Lodge, and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). In 1979, Local 2171 Flamborough merged with Local 5. And in 1980, Local 5 signed up Third Sector Recycling workers.

The Locals’ activism and outreach efforts also grew. In 1984, for example, CUPE National created a remembrance day for workers killed or injured on the job. The Day of Mourning, a United Nations initiative spearhead by Local 5 member and activist Ed Thomas, honours workers killed or injured on the job. Today, the Day of Mourning is commemorated around the world by approximately 130 countries on April 28.

Jim Clairmont talks about how he helped computerize the Local 167 office in the 1980s.

“The literacy program was done on your own time back then and that’s probably why there wasn’t much attendance. I convinced the executive to fight to get the employer to give workers some paid time for this. They agreed to pay for four hours a week, with the other four hours to be on the person’s own time. Later, a full paid day was won and enrollment in the literacy class went up.”

– Ed Thomas, Local 5 member and activist

Ed Thomas talks about how he helped the literacy become a paid-time program, instead of a voluntary one.

Equity and Diversity

By the late 1970s, equity and diversity had become key issues for CUPE. Statistics from 1982 showed that women earned just 59% of what men in similar jobs earned. In 1986, the province of Ontario enacted pay equity legislation. And in 1988, the City of Hamilton and region enacted its first pay equity plan. Job classes for all 7,000 employees, 52% of whom are women, were assessed by union and management representatives for inequities.

As early as the 1930s, inside workers, through their General Staff Association, were protesting regulations that forced married women to resign. And in the 1950s, Local 5’s Outsider newsletter urged members to have zero tolerance for racist jokes.

Efforts to include more diverse voices at conventions, on committees, and at the bargaining table also ramped up during this era. In 1988, CUPE created the Rainbow Committee to help address diversity issues. One of its founding members, Local 5 activist and President Fred Loft, was instrumental in the committee’s work and outreach.

“In the ’80s, our workforce was 70% female and their representation was certainly poor. They often talk in the union about the glass ceiling. It was prevalent there, I’ll tell you. Silly, silly things. We had a manager who insisted that women could only wear skirts that were so many inches above the knee. And he got away with this for years. A despicable person. But in those days…”

– Jim Clairmont, former Local 167 President and Treasurer

Preparing for the Next Fight

As the 1980s drew to a close, both Local 167 and 5 had achieved a lot against a difficult backdrop of deep cuts and runaway inflation. But even darker clouds were on the horizon.

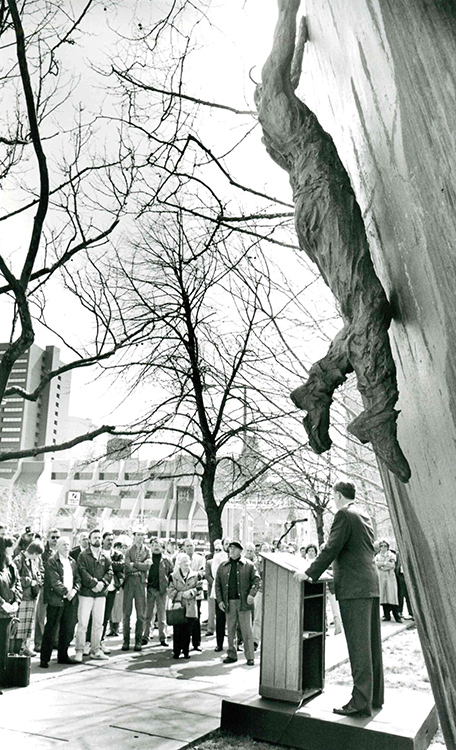

The Day of Mourning

At the 1984 Canadian Labour Congress Convention, a resolution was adopted declaring April 28 each year as a National Day of Mourning. The day honours workers in Canada who have been killed, injured, or disabled on the job. April 28 was chosen because on that day in 1914, Ontario enacted the first comprehensive Workmen’s Compensation Act in Canada. Day of Mourning Monuments have also been erected throughout Canada since 1984.

Today, more than 130 countries commemorate the Day of Mourning, and it is acknowledged by the International Labour Organization, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, and the American Federation of Labor. More than 14 million people around the world take part in the day to highlight the plight of more the two million workers in the world who die every year and the many millions more who become ill from unsafe working conditions.

Some Local 5167 members have also been killed on the job. Bill Morden was picking up garbage on Valentine’s Day in 1996 when a woman slammed her pickup truck into the back of his garbage truck, pinning Bill between the two vehicles. Paul Faustini fell off the back of his asphalt truck in 1997 while backing up on a work site. He was crushed and died as a result of his injuries. Mike Conneley suffered from exposure to toluene in the 1990s. He later had his leg amputated and then died of his injuries. And Joe Macaluso, who worked for the water department, fell off a roof in 1985 while hooking up water pipes to a house.

Many other members have also suffered serious injuries as a result of unsafe work over the years. A number of them never regained their health and never worked again.

Timeline

*bold events on the timeline are specific to Local 5167