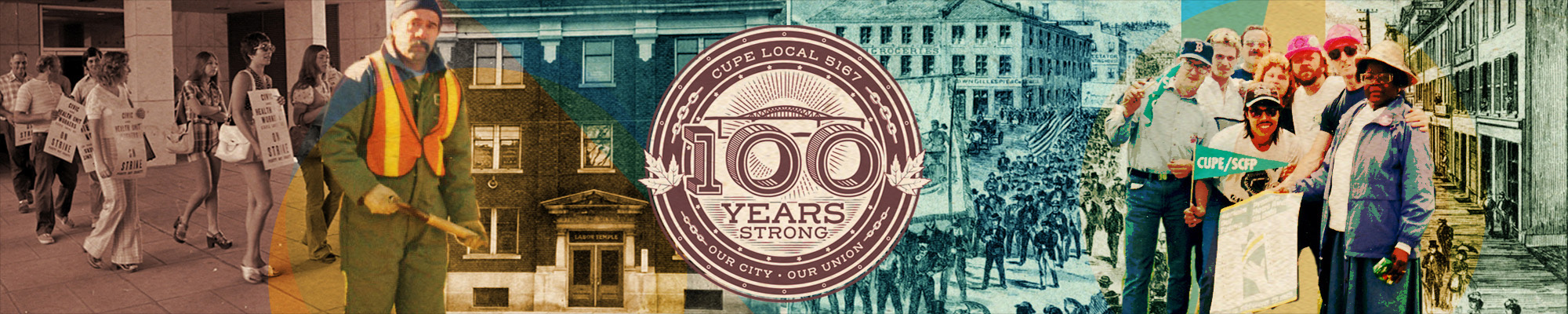

A New Era

Post-war Peace

The period after World War Two, from the mid-1940s until the early 1970s, was the beginning of a long stretch of prosperity and important gains for labour unions and working people. It was also a period of great political and social change, from the founding of the New Democratic Party (NDP) in 1961 (the successor to the CCF), to the establishment of medicare, to the birth of women’s-rights and civil-rights movements around the world.

Unionization rates in both the public and private sectors grew after the spike in union organizing during the war. In 1967, the federal government passed the Public Service Staff Relations Act, which extended collective bargaining rights to government workers. The majority of these workers now had the right to collectively bargain.

Rallying the Troops: 1950 Radio Broadcast

During the 1950 strike, a daily radio broadcast rallied union members, their families, and Hamiltonians to the strikers’ cause. The broadcast was written and delivered by Oliver Hodges on behalf of Local 5. Hodges was a CCL organizer who had moved to Hamilton in the late 1940s. This message was delivered on August 17, 1950:

“How Controller Hicks expects City workers to exist on wages of $1 an hour, when food costs have doubled, is beyond our comprehension. This is why the original union demands were for a wage increase of 10¢ an hour, which was reduced to 2¢ an hour during the final meeting with the City in a last minute effort to compromise and avoid a strike.

They are learning a new language — the language of the working people.

We would like to mention here our deep feeling of appreciation to the many citizens and businesses who have come to the picket line with gifts of cigarettes, milk, food, and soft drinks. The union has established a central canteen at 216 Barton Street for the receiving of quantities of meat, bread and sandwiches. A kitchen staff will make and distribute sandwiches from this point. Donations of food stuffs will be welcomed at 216 Barton Street East.

Goodnight until tomorrow night at 7:45.”

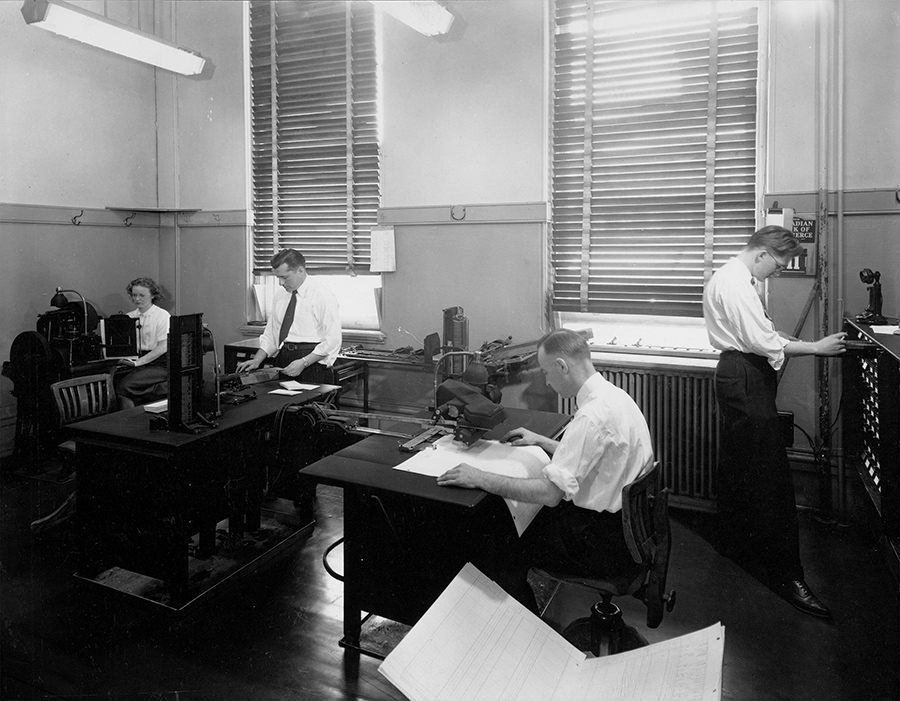

Working Life in Hamilton

As the 1960s approached, Hamilton had become the most highly industrialized city in Canada. Its industries boomed. The city’s steel industry expanded rapidly, fueling its economic growth. New waves of immigrants added to the city’s workforce and changed its complexion. By 1960, Hamiltonians’ average incomes had more than doubled, compared to the period before the war.

The History of Local 5’s Newsletters

Union newsletters have always been an important way to mobilize and educate workers. From 1945 until 1978, Frank Rogers, the Local’s Recording Secretary, wrote and produced The Outsider for members of Local Five. It was a colourful, unorthodox publication that had a broad reach. The newsletter was produced on a Gestetner machine, and Frank drew all of the cartoons.

In 1950, Hamilton’s Mayor Lloyd Jackson has this to say about The Outsider:

“It has distinct individuality, sometimes too much so, to my way of thinking. Sometimes your jokes are a bit ‘corny’ and sometimes a little ‘high’ but the fact remains you are expressing your own personalities and the publication is yours.”

For a few years in the early 1980s, Local 5 members Steve Booth, Bob Rose, Peter Wickett, and Ed Thomas reintroduced a newsletter to the Local: NewsFive, In the 1990s, the newsletter was reintroduced and named News Five Revived—still using Frank Rogers’s Gestetner machine.

Today, Local 5167’s current newsletter, Scoop, is produced using much more advanced technology. But it still has the same goal: engaging and mobilizing members.

The 1945 Ford Strike

After the war ended, workers in many industries continued to push for change. Two major strikes were instrumental to that fight.

On September 12, 1945, 11,000 workers at the Ford Motor Company plant in Windsor walked off the job and into a 99-day strike. The workers sought recognition of their union, the United Automobile Workers of Canada (UAW), and mandatory membership for all workers at the plant. Binding arbitration resolved the deadlock and resulted in the Rand Formula being implemented the following year. The Formula required all workers covered by collective bargaining contracts to pay union dues, meaning that the union no longer had to manually collect dues from every member.

The 1946 Stelco Strike

Just one year later, on July 15, 1946, thousands of Stelco workers in Hamilton walked off the job, pressing for higher wages, a 40-hour week, and the application of the Rand Formula. The strike lasted 85 days. Strikers were supported by many Hamiltonians, who joined them on the lines and fed strikers and their families. Hamilton Mayor Sam Lawrence was a staunch supporter of the strikers, leading a march of more than 10,000 people to the gates of Stelco in the middle of the strike.

Post-war Gains for Hamilton’s Civic Locals

The effect of these two strikes’ outcomes was significant, as their gains emboldened workers in many other sectors and cities. Both Locals 5 and 167 sought to have the Rand Formula applied in their first rounds of bargaining after the strike, in 1946 and 1947. Although Hamilton’s Board of Control fought the measure, by the end of the decade, the compulsory check-off was in place for both Locals, and for many other unions across the country.

Wildcat! The 1949 Strike

On June 13, 1949, Hamilton’s garbage workers walked off the job in a half-day wildcat strike. The strikers wanted 44 hours’ pay for 40 hours of work each week — something they had long been seeking — and an increase in their hourly wages from 79½ cents to $1.00 an hour.

In 1949, Local 5’s first contract expired, and new contract talks stalled. In response, on June 13, Hamilton’s garbage collectors held a half-day wildcat strike. After the strike, the new agreement bargained by the Local 5 achieved this new rate and other major gains, too. Five statutory holidays per year were added to the existing six, and a reduction of five years (from 20 to 15) in the length of service required to obtain three weeks’ summer vacation was put in place.

A Long, Hot Summer of Discontent

The temporary peace won in 1949 would not last, however. Local 5’s 820 members were still seeking a five-day, 40-hour week with same take-home pay as a 44-hour week, a raise of 10 cents/hour across the board, a minimum hourly rate of $1.12, and a number of other concessions.

This time, the city’s Board of Control dug in, though. So, on August 10, 1950, Local 5’s garbage workers walked off the job after lengthy negotiations, conducted over a number of months, finally broke down. The strike lasted 39 days and resulted in temporary dumps being set up around the city as more than 2,500 tons of garbage went uncollected and Hamiltonians demanded action from Mayor Lloyd Jackson and the Board of Control.

In response, the mayor threatened the use of police to protect the private trucks the city had hired to haul garbage to the temporary dumps. Strikers and their supporters moved to blockade the dumps, and the mayor soon backed down.

Although the long, hot summer of smelly garbage had tested the patience of many citizens, most Hamiltonians supported the strikers and their demands. Families joined picketers on the line, and food, money, and other supplies were donated to the Local.

Although the 1950 strike achieved some important goals, it had been hard on members, too. Many members had been forced to borrow money from family, friends, and their Local during the strike. In 1955, Local 5 decided to forgive more than $5,000 of personal loans it gave to its members during the strike.

Emerging from the Strike

Over the next two decades, both Local 5 and 167 fought for and won many important gains. In 1956, Local 5 signed up workers at the Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG), and negotiated their first collective agreement. By 1958, the Local represented workers in a number of city departments, from cemeteries, to parks, to waterworks and sewer maintenance, to flushers, sweepers and city garage workers. And Local 167 continued to grow. By 1967, it represented 2,500 civic workers.

By the end of the 1960s, rising inflation rates began to erode workers’ wages. Contract negotiations tried to keep up with these increases, but it was never enough, it seemed. In 1967, Local 167 sought a wage increase of 9% and 6% over two years. And Local 5 fought to increase its basic labour rate by 20 cents an hour in each of 1968 and 1969.

Over time, the two Locals also made significant and lasting attempts to work together at the bargaining table. In 1959, for example, Local 167 created a Unity Committee. It met with Locals 5, 288, and 700 throughout the year to discuss how they could work together. And in 1963, the two Locals exchanged letters and attended each other’s meetings in the lead-up to negotiations with the city.

Strengthening Bonds off the Job

Throughout the postwar years, civic workers continued to build connections outside of the workplace, too. Both Locals added more events to their members’ social calendars. These included large dances and socials, as well as Christmas parties for members and their families. Local 167’s Christmas Tree Party was well attended, with hundreds of members and their families coming out to talk to Santa and share gifts. And yearly summer picnics for civic workers continued to be held, attracting thousands of city workers to Burlington Beach and other locations.

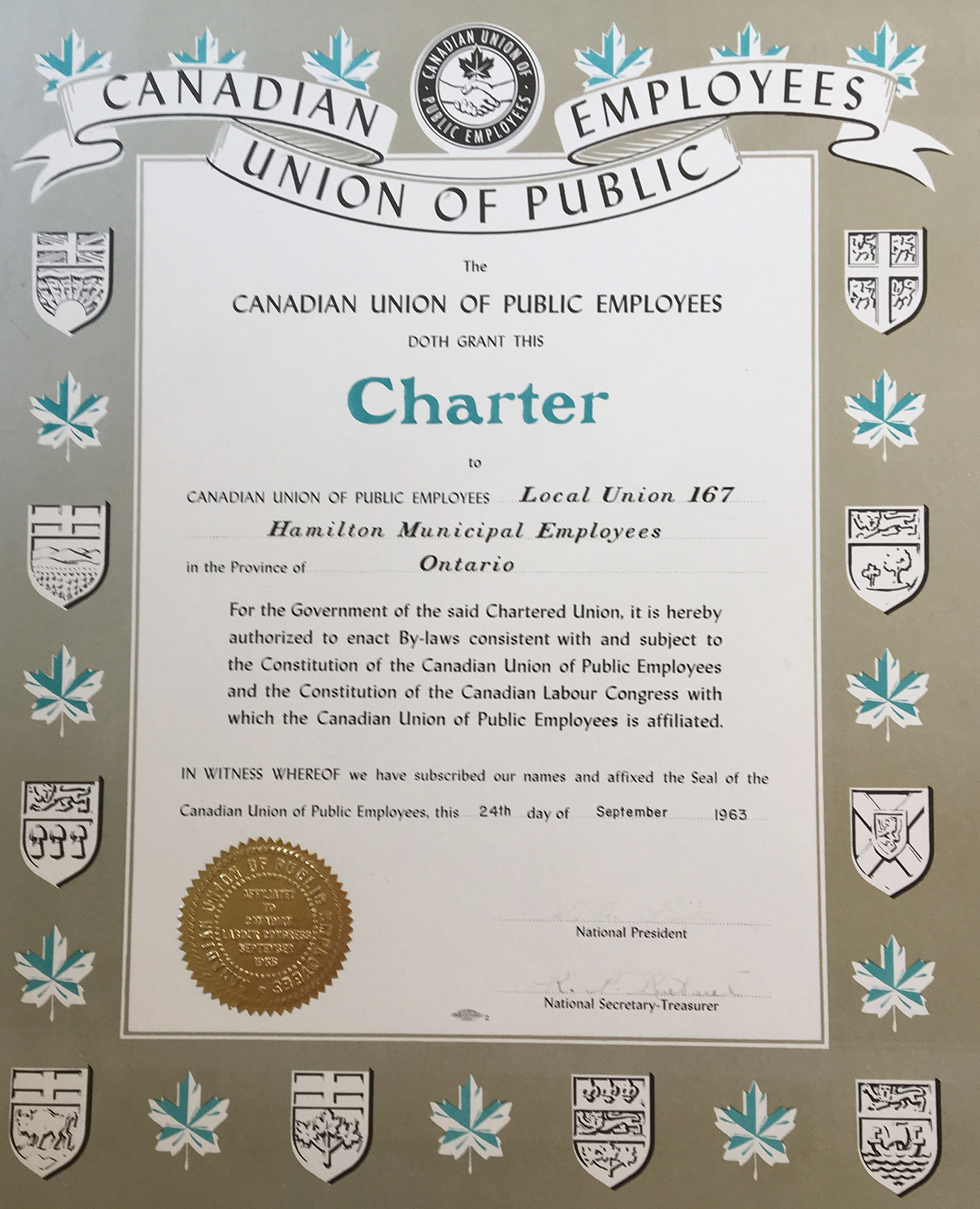

A New Canadian Union is Born

The late 1950s and ’60s also saw a lot of change on the broader labour front, as more public sector workers became organized and union membership grew significantly.

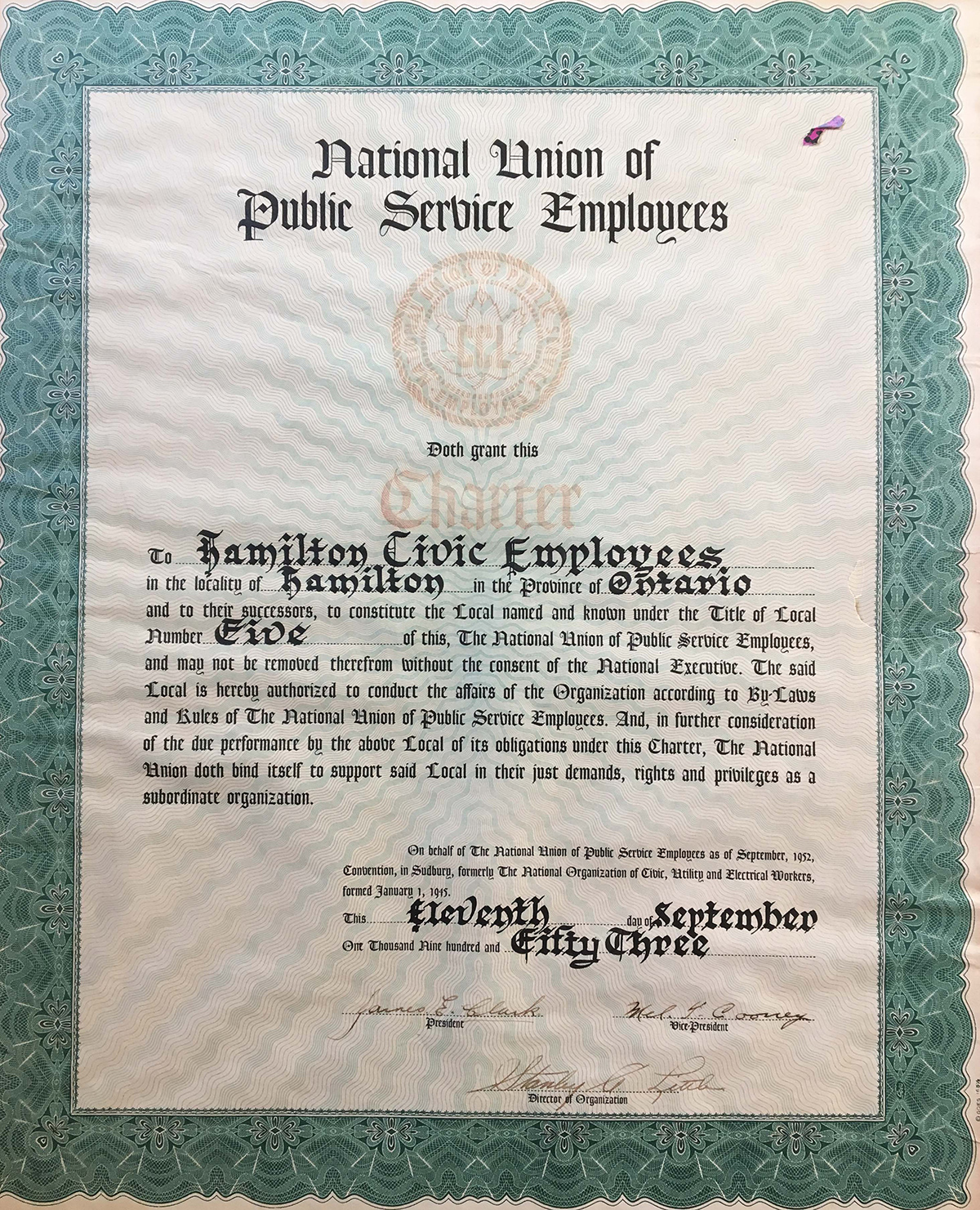

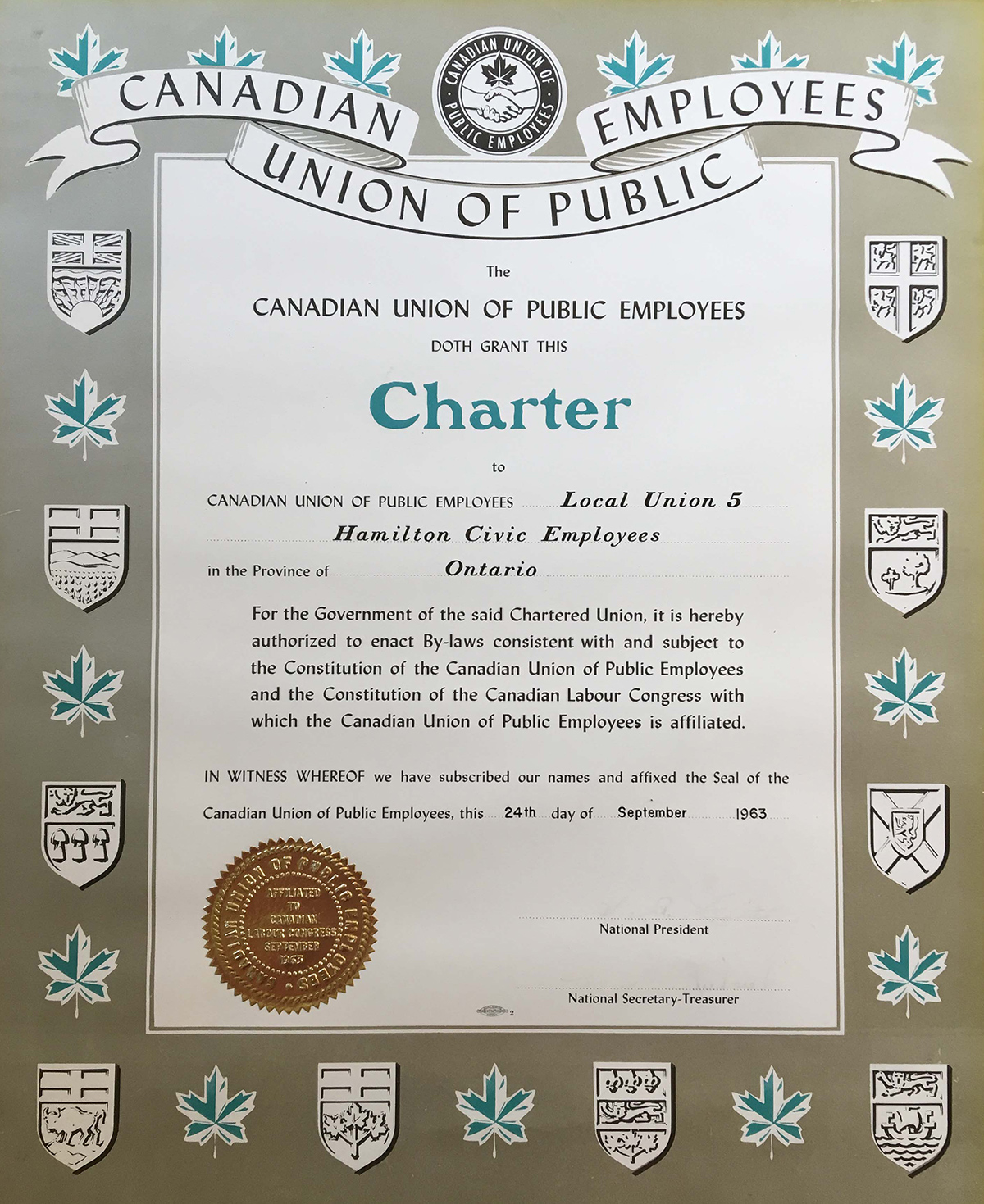

In 1953, the National Organization of Civic, Utility and Electrical Workers changed its name to become the National Union of Public Service Employees (NUPSE). In 1956, the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada and the Canadian Congress of Labour merged to form the Canadian Labour Congress. And after a seven-year process of negotiation, in 1963, NUPSE and NUPE merged to become the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE). NUPE’s Robert Rintoul was elected Secretary-Treasurer and NUPSE’s Stan Little was elected President. Local 5’s Recording Secretary, Frank Rogers, played an important part in the merger.

Over the next decade, the new union signed up thousands of municipal and provincial workers, as well as workers employed in hospitals, schools, day cares, nursing homes, libraries, social service agencies, and other related sectors of the economy.

CUPE also began to focus on issues of equality and greater political engagement, including pressing for equal pay for work of equal value.

Road Blocks Ahead

By the end of the 1960s, Hamilton’s civic workers had achieved a number of important gains. But the 1970s would test those gains, and the workers’ resolve. Oil prices rose steadily and inflation ballooned, and governments at all levels sought to cut costs by implementing a series of hardline wage and price controls.

Timeline

*bold events on the timeline are specific to Local 5167