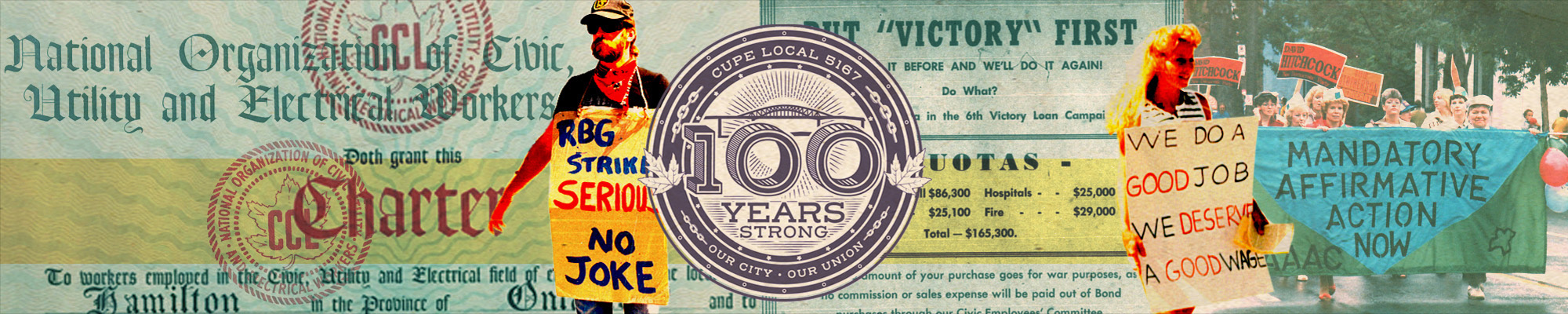

The Birth of Local 5

War, Revolution, and Change

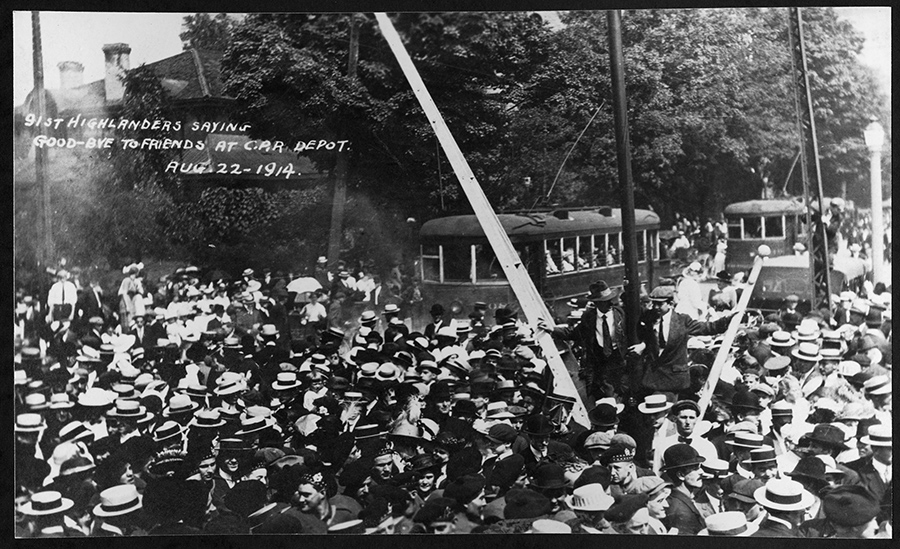

World War One began in 1914. Hamiltonians were important contributors to the war effort, both in the many recruits who joined the fight and in the manufacturing of war materials. By the time the war ended four long years later, the young men who returned home from the front had seen unimaginable horror. It changed their lives and their expectations.

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia showed many working people around the world that there was a real need for change. Workers in Canada took action to demand their rights in the midst of these changes. In August 1918, the Vancouver General Strike, the first general strike in Canadian history, was organized to protest the killing of draft evader and labour activist Albert Goodwin. And in 1919, the Winnipeg General Strike and the creation of the One Big Union were important ways that workers fought back.

Workers used more organized ways to seek change, too. Building on working people’s growing political strength, the Trades and Labour Congress helped found the Canadian Labour Party in 1917. And in 1921, NUPSE, the National Union of Public Service Employees, was created.

Working Life in Hamilton

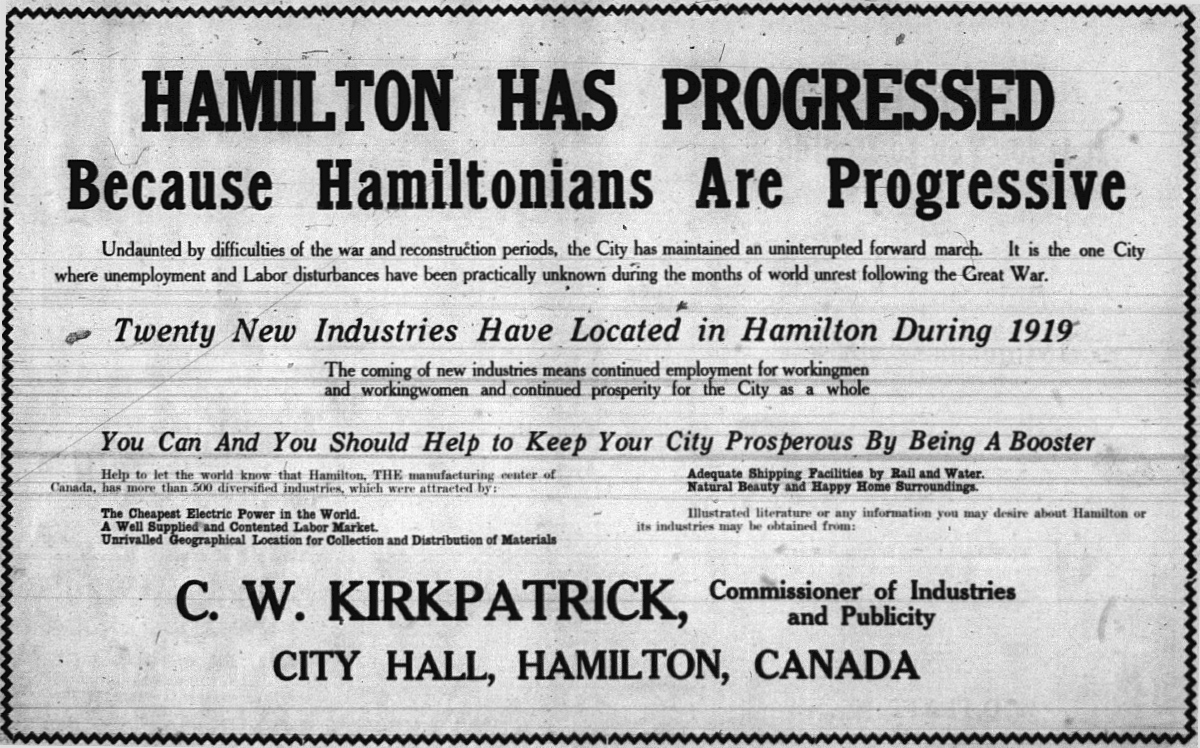

By 1915, many industries began to boom as the government increased its military spending and Canada became an important supplier of materials to the war effort. The recession of 1913 and high unemployment were soon replaced by a labour shortage as industries looked for workers. New technologies were introduced during the war, and workers had to learn different skills and ways of working.

The 1920s were also a time of change in the workplace for both inside and outside civic workers. Inside workers, for example, were introduced to new machines such as typewriters, and their work became increasingly deskilled. And outside workers had to master new equipment, such as gas-powered lawnmowers, and new ways of working, too.

At the same time, some work — especially for outside workers — was still mostly done by hand, and was back-breaking. Unpaved roads were still the norm in many cities, and the work of keeping them passable was not mechanized. And large groups of men were still put to work shovelling snow on the city’s main streets and removing it using wagons.

By the early 1920s, another severe recession had taken hold. Hamilton’s unemployment rate climbed to 15% by 1921, and many Hamiltonians who had gone overseas to fight in the war found themselves back at home with no work prospects and unclear futures.

Outside Workers Organized

After World War I, and as the recession set in, many civic employee associations become more militant and organized along traditional trade union lines, like their peers in the private sector.

A new Hamilton civic employees’ union was born right at the end of World War One and into the midst of this upheaval. In 1918, the City of Hamilton outside employees were chartered as the Civic Employees Union Local 16208, under the American Federation of Labor (AFL). William Nolan was the Local’s first president.

Fighting for Better Working Conditions

By 1918, as wartime inflation drove up the cost of living for Hamiltonians, many outside workers began fighting for higher pay and better working hours. Street cleaners, for example, fought for a raise from 30 to 35 cents an hour and a guarantee of more regular hours. In 1919, sewer diggers walked off the job for two days in May to back their demands for a reduced working week, from 48 to 44 hours, an eight-hour day with nine hours’ pay, and a pay raise to 45 cents an hour. The diggers were joined in their strike by asphalt, sidewalk, and street cleaners.

In 1920, grave diggers walked off the job to demand a raise from 45 to 55 cents an hour, and to get rid of the section system (where grave diggers had to stay in certain sections of the cemetery so that they could answer questions from the public about the location of graves).

Inside workers fought to see their wages increased, too. In response, Hamilton city controllers set minimum and maximum salaries for male and female clerks. Women’s yearly rates were set at $500 and $840; for men, the rates were $600 and $1,200.

Gaining Benefits

Civic workers won other important gains after the war, too. In 1922, the city proposed a new retirement pension plan for its workers. Although the new plan was not put into place right away, it was an important first step. At the time, no matter how long a worker had been employed by the city, the maximum pension they could receive was three years’ salary. Under the proposed idea, the city would set up an initial grant to fund the pension. Then, civic workers would contribute to their pension funds during their working years so that they could receive a pension from retirement until death.

Forging Ties off the Job

As they always had, civic workers strengthened their bonds outside of work, too. Annual picnics, Christmas parties for members and their families, and dances continued to be popular activities. Inside workers created a five-pin bowling league and competed against other civic leagues in Toronto and other cities. In 1923, for example, six teams from the Hamilton City Hall Employees’ Association beat six teams from the Toronto City Hall Employees’ Association Hamilton. Baseball games and other sporting events were also popular with civic workers.

Dark Clouds on the Horizon

After World War One, Hamilton’s civic workers won significant gains in working hours, salaries, and some benefits. But all of this would change by the end of the decade.

Timeline

*bold events on the timeline are specific to Local 5167